Saving the Dakota language, and saving a worldview

A teaching specialist at the University of Minnesota serves as project director for the first comprehensive Dakota-language dictionary app.

Reid Forgrave | Star Tribune | February 25, 2023

When Joe Bendickson was growing up, first on the Lake Traverse Reservation near the Minnesota-South Dakota border and then in St. Paul, he did not speak Dakota, his ancestral tongue. Few did. Generations of Native Americans had been institutionally raised in boarding schools, which banned students from speaking their native language. The Dakota language was becoming extinct.

As he grew older, he became more interested in his ancestry as a member of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate tribe. He asked his grandfather to give him a Dakota name. His grandfather chose Šišókadúta, which means “robin red.” At 19, Šišókadúta took a Dakota language class, which inspired him to major in American Indian Studies at the University of Minnesota.

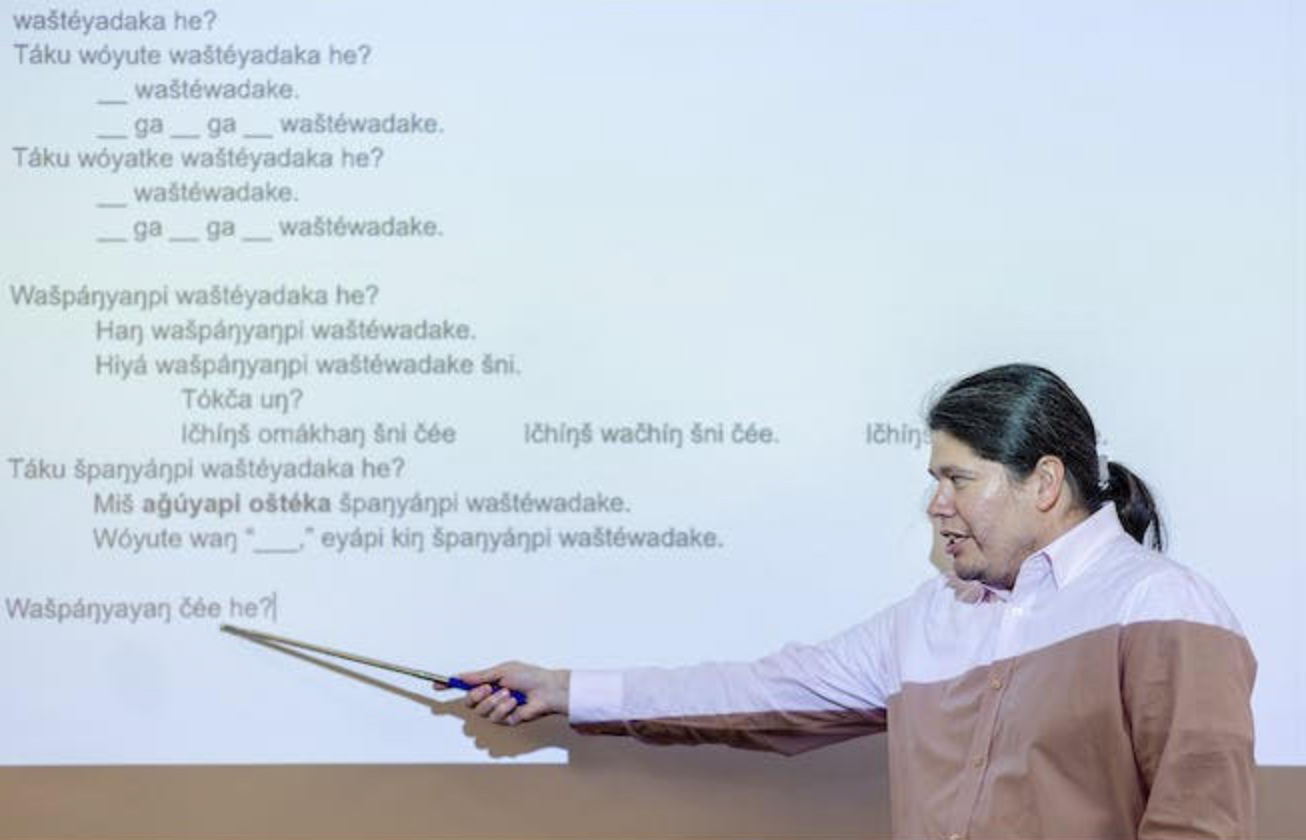

Today, Šišókadúta teaches the Dakota language there and serves as project director for the first comprehensive Dakota-language dictionary app, unveiled this month. And he continues his quixotic quest, dedicating his life to saving a language he didn’t grow up speaking — which he hopes can preserve the identity of his people.

“It just seemed to be something you could do to reverse all the horrible things that happened to our people and our language,” Šišókadúta said. “This is something good you can do.”

Some 7,000 languages are currently spoken worldwide. According to the Language Conservancy, a nonprofit promoting language diversity worldwide, 90% are at risk of extinction in the next century. Of the nearly 500 languages once spoken in the land that’s now the United States, only about a dozen Native American languages have a chance at surviving beyond 2050, the organization reports.

In Minnesota — a Dakota word translated as “where the waters reflect the skies” — Dakota had once been the primary language spoken. Now there’s only one elder remaining in the state who is a first-language Dakota speaker.

“We’re all in a boat trying to get to this mythical place where this language is spoken again, and all you can do is ask people to join you in that journey,” said Wil Meya, CEO at the Language Conservancy. “We’re against this juggernaut of the majority languages in the world that are only increasing in utility and use. It’s hard to stand up to them in any meaningful way. And yet we’re doing it.”

“Linguistic heritage is passed down for tens of thousands of years,” Meya continued. “When that’s lost, all the nuance and stories and world views are lost.”

The biggest success story of a language resurgence is Hebrew. Hebrew was once just a liturgical language only spoken by a few hundred rabbis until the Zionist movement revived it and the formation of Israel solidified it. Now there are millions of fluent Hebrew speakers around the world.

New Zealand started a formal revitalization of the Maori language in the 1960s; now there are universities and television stations and camps in Maori. And Hawaiian has been in a state of revitalization for decades, becoming a significant part of Hawaii’s modern cultural identity.

Šišókadúta doesn’t just talk the talk. The 44-year-old is living the life of a language conservationist. He speaks Dakota at home with his wife and children. His 4-year-old son attends a new Dakota-language preschool at the university. He teaches 40 or so students each semester, mostly students of Dakota heritage. He served as project director of the free app, Dakhód Iápi Wičhóie Wówapi, a Dakota-language dictionary with 28,699 Dakota entries. It was funded with a Minnesota Indian Affairs Council grant.

Building standardized dictionaries is the foundation of resuscitating a dormant language. Meya calls this dictionary a symbol of hope: “the hope of the Dakota people to reclaim and rebuild their language,” he said.

This language isn’t simply different ways of saying the same things in English, Šišókadúta said; certain meanings get lost in translation, which only underscores the importance of language diversity.

English is unable to fully express meanings of certain Dakota words, he said, especially words describing the spiritual plane. For example, “Wakháŋ Tháŋka” means something inexplicable and mysterious, and it explains spiritual concepts such as God. “Uŋčí Makhá” is a Dakota word for Earth — literally translated as “Grandma Earth,” because life comes from women.

And the worldview of the Dakota language can be expressed in “mitákuye owás’iŋ,” which means “all are related.”

“We have this belief that we come from the stars, related to everything on the planet,” Šišókadúta said. “All the atoms in our body are interrelated to everything else on Earth. That’s a unique world view you might not get if we didn’t have this language.”

As a younger man, when Šišókadúta learned what colonization and assimilation did to his people, it was depressing. What could he do to improve the legacy of these awful things from generations ago?

“For me,” he said on a recent morning, shortly before walking into Nicholson Hall for a beginning Dakota class, “it was to learn this language and help bring it back. Revitalize it, grow it. It’s a way to reverse history.”

Seven students in his class repeated after Šišókadúta as he pronounced Dakota words about cooking: “okáda,” which means pouring something granular like sugar, and “ičáhiyA,” which means stirring things together like stir fry, and “kačóčo,” which means a more vigorous mixing, like for dough or scrambled eggs. Students spoke to each other in Dakota.

RickyMae Littlest Feather, a sophomore, was born and raised near the Red Lake Reservation, which is Ojibwe territory. Her great-great-great-great-grandfather, Mazaadidi, was one of those exiled after the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. Mazaadidi — along with his wife, Pazahiyayewin, two young children and Pazahiyayewin’s elderly mother — was forced to march to Mankato, where 38 Indians were hanged. President Lincoln pardoned Mazaadidi from the hanging, and he was sent to a concentration camp.

“I can remember sitting in the back of my grandmother’s car, and she was talking about how during that march, when they passed through towns, white people would take pots of boiling hot water and pour it on my family,” Littlest Feather said. “I’ve been familiar with the history of my family since I was a little kid.”

Now, as an early childhood development major, she’s working at the Dakota-language child care that Šišókadúta’s son attends.

“It makes me want to cry, having hundreds and hundreds of years of our culture stripped away, and I’m finally getting the opportunity to have it back,” she said.

For Šišókadúta, this is exactly the point: He’s planting cultural seeds in a younger generation, who can then pass it on to the next.

“We want it to stay a living language, one that’s passed down from generation to generation as a spoken language,” Šišókadúta said. “We don’t want it to become something that remains in books and recordings only. We’re all racing against time.”