Local Conservancy Now Saving Indigenous Languages Worldwide

Michelle Gottschlich | Limestone Post | April 26, 2018

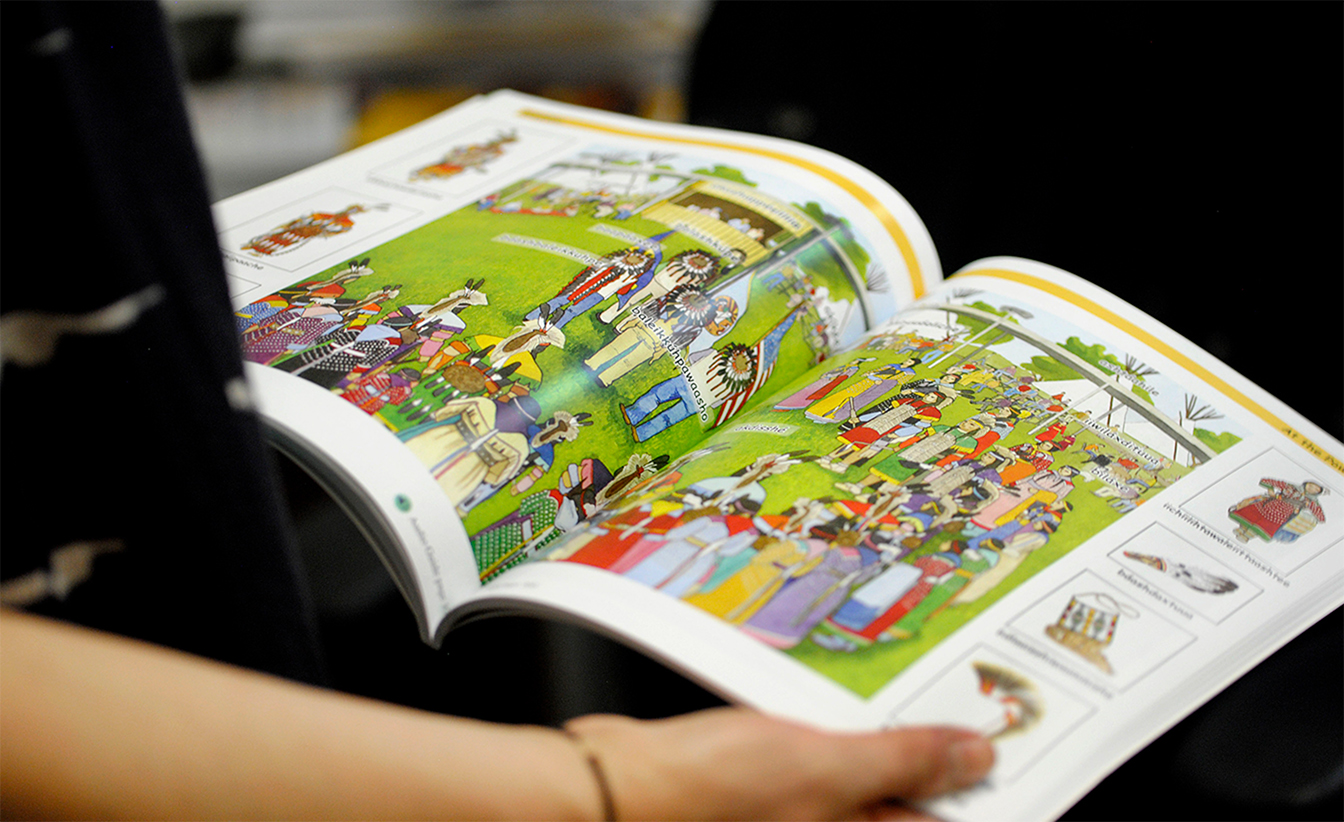

Bloomington’s The Language Conservancy (TLC) works to preserve Native languages that would otherwise be lost. Pictured here is one of the many books the organization produces to assist those trying to learn specific languages. | Photo by Nicole McPheeters

“Excuse me, are you Kevin?” The man has long braided hair, a rolling suitcase, and an armful of colorful hoops. We’re in the lobby of the Monroe County Public Library. He responds with a politely blank “Yes.” Of course he is Kevin.

Before his performance, I sit down for a short interview with Kevin Locke, who is Lakota and Anishnabe. We talk about the stigma that comes out of poverty on reservations and why so many Lakotas don’t speak Lakota anymore. Locke himself didn’t learn his native language as a child. Now he travels the world performing Lakota songs, often at school assemblies and festivals, where he plays the Indigenous Northern Plains flute and dances with traditional hoops, a dance style that illustrates “the roles and responsibilities that all human beings have within the hoops (circles) of life.” Locke, who is from the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in South Dakota, is commonly called a “cultural ambassador,” the phrase even appears on his website, but he doesn’t fully agree with this terminology. The last thing he wants to do is advocate for one specific culture or agenda. He just wants kids to be who they are.

“This is how you would say ‘decolonize,’” says Locke. “What you’re really saying is you go back to the reality. It has nothing to do with nationalism or native pride. It has zero relationship to that. You go back to being a human being.”

Over the past 50 years, indigenous languages have been rapidly disappearing. The reasons range dangerously wide — the enduring effects of 19th-century colonialism, mandatory English-speaking boarding schools of the 20th century, popular parodies of indigenous peoples, institutionalized poverty, the U.S. government’s disregard for indigenous nations, and so on. Hundreds of languages are already gone. The practice of others continues to be stamped out and stigmatized into extinction.

Locke’s performance in the library’s auditorium is my unofficial introduction to The Language Conservancy, a national nonprofit organization for the revitalization of indigenous languages.

The Language Conservancy, or TLC, was founded in 2005 to address the loss of indigenous languages on a national level. It creates learning materials, provides teacher trainings, fundraises, and advocates for tribes across North America. Locke serves on the board. The majority of TLC’s staff is made up of a diverse field team of linguists, teachers, and native speakers who live and work across the U.S., but its small administrative staff is headquartered in Bloomington.

Also attending Locke’s performance is TLC’s public relations and communications director, Mitch Teplitsky, who invites me on a tour of their headquarters.

The building at 2620 N. Walnut is a small yet dizzying complex of offices and wood-paneled hallways. I become quickly disoriented as Teplitsky takes me around to introduce his colleagues. First I meet Elliot Thornton, IT specialist. When an indigenous tribe hires TLC, linguists record the tribe’s entire language in an exhaustive process called Rapid Word Collection, a method of lexicon development that allows linguists to record thousands of words during a two-week-long workshop with members of a native language community. The collected words are entered into a database and organized into semantic domains (universe/creation, person, language and thought, social behavior, daily life, etc.). The collection is uploaded online where community members can access and add to their lexicon, and where TLC — specifically, Thornton — will continue to process the material.

Thornton’s office has the markings of someone who never stops working, as does every office I will see. The density of work per square foot, per person, per moment, is impressively baffling. Thornton explains that he and a team of interns will spend nearly a year processing the language material from a single collection. At the same time, Thornton also develops language learning apps and other multimedia technologies for learners. He shares this material with the indigenous tribes as well as the design team in an office down the hall.

There, TLC’s graphic designer Allison Horner shows me an illustration she’s drawn of a traditional native garment. She describes the level of detail; every material choice gives information about the tribe. It can be overwhelming to get right — a sentiment seconded by Bob Rugh, Horner’s office mate and TLC’s publication specialist. Together, Horner and Rugh design physical learning materials such as textbooks and classroom aids. They work with native speakers to cross-check their materials’ accuracy, edit after edit. In the next room over, the texts are printed and bound on one of two printing rigs, each the approximate length of a Chevy Impala.

Elsewhere in the labyrinth is Rebecca Mueller’s and Teplitsky’s office. Mueller is TLC’s event coordinator; she organizes teacher trainings, summer institutes, and other events for indigenous communities. Teplitsky’s role as PR and communications director is a sort of odd job for an organization that has kept its profile barely above a whisper for the past 13 years. TLC works in the background of tribes’ own revitalization efforts as a sort of support team. “We want to forefront the tribes themselves,” explains Mueller. “Here, we’re just the administrative side to help them kick-start.”

Development Director Courtney Foster joins our chat. TLC wrote 130 grant proposals last year. Foster explains how indigenous tribes are greatly underserved if you consider that only a half percent of all philanthropy goes to these groups, yet they make up one percent of the total population. A primary function of TLC is to fundraise for indigenous tribes regardless of whether any portion of those funds return to TLC via the purchase of learning materials. If a tribe wants to purchase materials but can’t afford to, the grant team will raise money for them. Additionally, in most cases, tribes also own the rights to the materials they purchase from TLC, allowing them to maintain independence as they rehabilitate their native languages and traditions.

Another primary function of TLC is to bring awareness to endangered indigenous languages and the desperate need for revitalization, which is where Teplitsky comes in. In response to mass language loss (and perhaps in some part owing to TLC’s success at raising awareness), the United Nations has named 2019 the Year of Indigenous Languages. In April, The Language Conservancy participated in the 17th session of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) at UN Headquarters in New York. While there, they hosted a panel discussion about TLC’s work and vision, which was live-streamed around the world. “We are aiming to be key UN partners, to help bring more attention to endangered languages worldwide, before it’s too late,” says Teplitsky. “Also as a result of our participation at the UN, we are getting approached by more and more language communities worldwide — from Quechua in the Andes, to the Fiji Islands — to help develop projects for them.” TLC plans on branching into that international work in the coming year, which, I’m told, is no small logistical feat. It’s almost hard to imagine this tiny office, already running full tilt, adding international advocacy to its operations, but these are no ordinary office workers.

“Everything’s changing fast,” says Locke, the night of his performance. “What’s happening is people are awakening. Like the whole thing at Standing Rock — all these big corporations try to squelch it, but all they really succeeded in doing is turbo-charging everything. It just added momentum. It’s like trying to hold back the light once the light’s released, it’s like trying to hold back the spring when the spring comes. No matter what you do, you can’t hold it back once it comes out.”