Revitalizing Apsáalooke

As Native languages face threat of extinction, Crow people work to keep theirs alive

Caroline Elik | The Sheridan Press | June 29, 2023

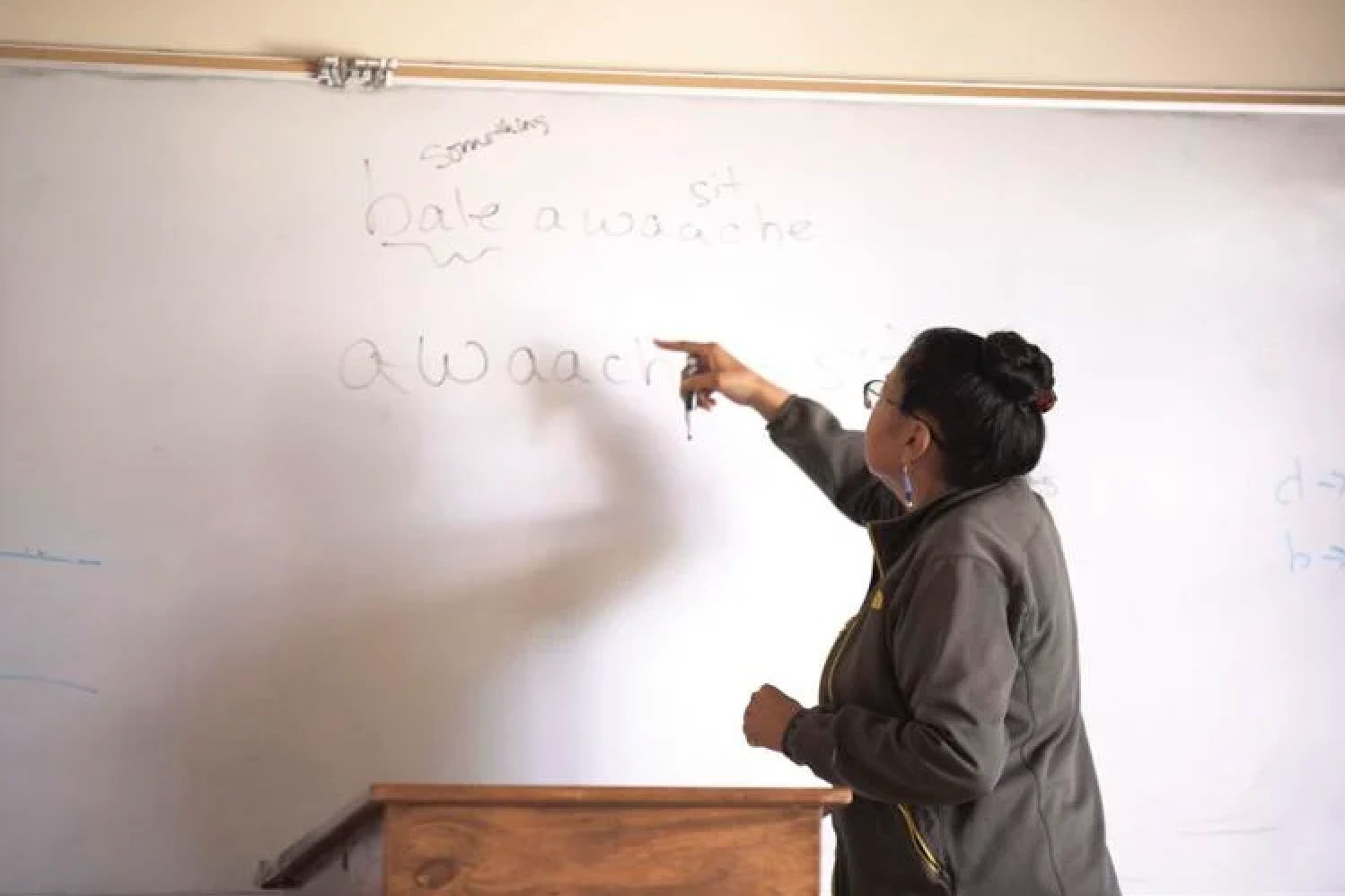

Roanne Hill teaches a class at the Crow Summer Institute at Little Big Horn College in Crow Agency, Mont., Wednesday, June 28, 2023.

CROW AGENCY, Mont. — The Crow Summer Institute — an annual multi-day workshop hosted by the Crow Language Consortium at Little Big Horn College — is back for its eleventh year, bringing together Crow language experts, beginner learners and people dedicated to helping the Crow language flourish.

The goal of the Crow Summer Institute is to improve the preservation of the Crow language — known as Apsáalooke — by building upon different resources, helping instructors refine their teaching skills and providing students at varying levels of proficiency learning opportunities. Classes are being held this week online and in person at Driftwood Lodge on the Little Big Horn College campus. Another session of workshops will also happen July 10-14.

Crow teachers at the institute said keeping the language alive is also a way of ensuring the vibrancy of Crow culture survives for future generations. The Language Conservancy — a nonprofit that helps support the Crow Language Consortium (CLC) — says more than 200 Native American languages have become extinct in the past 400 years, and the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) estimates just 20 native languages will be spoken by 2050.

When languages die or become endangered, many unique cultural and historical concepts fade with them. Many Crow community members recognize the critical need to protect the heritage of their language and the customs that go hand-in-hand with it.

Importance of language in Crow culture

Native languages are part of the essence of tribal identities, according to the NCAI. They help shape beliefs, ideas, governing systems and almost every other cultural characteristic of a tribe.

Velma Pretty On Top, a consultant to the CLC and cultural education coordinator at St. Labre Indian School, said that’s why it’s important not just to sustain the Crow language, but to improve it. She said the institute does this by facilitating collaboration between Crow speakers to determine best grammar and spelling practices, teaching methods and resource materials.

“We’re trying to revitalize the language. A lot of it has been lost,” Pretty On Top said. “Language and culture go together, and we have a beautiful culture … we’re going to lose both if we don’t use it and practice it and speak it. So it’s my passion.”

Vance Crooked Arm, a teacher at the summer institute said many traditional Crow ceremonies must be performed in the Apsáalooke language. Many of the tribe’s stories and oral traditions are also communicated in Crow, and the loss of the language would severely negatively impact the well-being of the tribe.

“If we lose our language, we’re not Crow anymore,” Crooked Arm said. “We lose our identity, we lose our way of life.”

Violence led to Native American language loss

(Content warning for mentions of abuse against Native American children)

The decline of the Crow language — and all Native American languages — can be traced back to oppression by early European settlers and the U.S. government.

In 1819, the U.S. government passed the Civilization Fund Act, which eventually ushered in an era of federally-funded Native American boarding schools designed to “civilize” indigenous children by attempting to assimilate them into mainstream American life. The schools were run by the government and Christian missionaries, who operated them with the goal of erasing all tribal cultures and practices from the lives of Native American children.

Children were often forcibly taken from their families and sent to boarding schools, which were known for being ruthless hubs of trauma and death. Many children suffered severe physical abuse for displaying any behaviors related to their culture — like speaking their native language.

An investigation published in 2022 from the U.S. Department of the Interior determined “the boarding school system discouraged or prevented the use of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian languages or cultural or religious practices through punishment, including corporal punishment.” Indigenous children aged eight and older were at increased risk of being punished at school for using their native language because they had higher proficiency in it, making them more likely to speak it.

Bob Rugh, director of Crow operations for The Language Conservancy, said these boarding schools, as well as other efforts to eradicate Native American lifestyles and beliefs played a significant part in the steep decline of tribal languages. He said after the Apsáalooke language was taken away from young people during the mid-19th and 20th centuries, many grew up with a sense of shame when it came to reading, writing and speaking Crow.

Rugh said within the past several decades, a renewed sense of pride in the Crow language has taken hold among tribe members. However, challenges remain when it comes to educating people — especially the younger generation — on learning the language. Fewer children grow up in households where Crow is the primary language spoken, and while it’s taught at most public schools on the reservation, a lack of complete immersion can hurt students’ proficiency.

“It has to be maintained on a daily basis, and it has to be spoken in a household,” Rugh said. “A lot of kids have lost the language because they’re not practicing it every day. I think online media has done a lot to really stifle that, because we’re just bombarded with English all the time.”

Modern resources at the forefront of Apsáalooke language conservation

The CLC has worked to make various teaching materials and classes on the Crow language accessible to anyone wanting to learn or brush up on their skills.

The Crow Summer Institute hosts classes over Zoom as well as in person, with people from as far away as Scotland logging on to participate. The CLC has also produced curriculum materials such as children’s books, textbooks, flash cards, audio CDs and more. The Crow Mobile Dictionary app allows users to search for words, listen to the pronunciation and cross-reference English words.

Last year, the CLC also released a print edition of the Crow language dictionary with more than 11,000 entries — a monumental success, as 1970 was the last time a version of the dictionary had been released. The older version contained just 2,000 entries.

Montana State Rep. Sharon Stewart-Peregoy, D-Crow Agency, who teaches Crow Studies at Little Big Horn College, said educating younger generations is key to making sure the Crow language continues to live on. She emphasizes to her students that the mobile dictionary app, online videos and e-learning courses are geared toward them, and to practice even if they’re nervous to make a mistake or mispronounce a word. She credited the Crow Summer Institute, the continuing efforts of the CLC and the heartfelt passion of those committed to the Crow language for helping it survive and thrive despite historical injustices that threatened its existence.

“It definitely has had an impact,” Stewart-Peregoy said. “The preservation of the language and culture is paramount. If we have a concerted effort … we can do it, but it’s not something that will happen overnight. We just have to stay the course and keep moving.”